COMMUNICABLE DISEASES: The Resurgence of TB

By Saada Branker

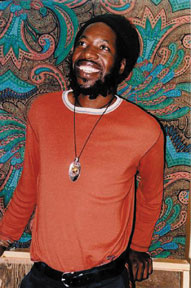

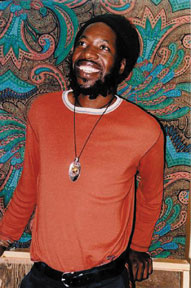

Like so many artists, Munya Madzima came to Canada inspired. He was ready to blow up, splintering the Toronto art scene with his multimedia sculpting. The young Zimbabwean built his big ideas for small companies. He hoped his knack for using up space, by combining various materials, would throw people off, as great art does. Recently, at a Toronto exhibition, almost 300 people took in his work. He knew such exposure could only be a good thing. But another kind of exposure has been weighing heavy on MadzimaÕs mind: a deadly disease that stalks his friends and family back in Africa.

Specifically, a cousin in Harare had stopped taking his TB medication, because he felt much better. Little did he know he needed to continue the antibiotic treatment for a few more months -- something his doctor didn't emphasize. From across an ocean, Madzima was told his 35-year-old cousin was on a grueling schedule, handling what seemed like 100 pills in order to fight a TB strain he had inadvertently made stronger.

"I haven't sent him a letter yet," he had said sadly, not knowing that at the time he uttered these words, his 35-year-old cousin had just died. Today Madzima's sadness is compounded by the fact that his cousin succumbed to what was initially a treatable disease. Still, the native Zimbabwean has no illusions, for he lost uncles in the same manner. He knows, had that letter been written earlier, along with the words of comfort, there would have been a good-bye.

There are no music concerts, or fashionable ribbons for TB. It doesn't even make the top five listing of sexy diseases, not when everyone is still obsessing on the just-as-important AIDS, E-Coli, Ebola and even Foot & Mouth disease. But tuberculosis, also known as TB, is a stealthy killer. Still. That's because 80 years after the first vaccine was developed from a bovine cousin of the bacterium, TB has resurged with renewed strength. It's called a multi-drug resistant strain. Just when we thought it was on the verge of obscurity, TB seems to have made a devastating comeback. Every year, almost three million people throughout the world fall victim to it. It's an epidemic proportion, proving one thing: TB never really went away.

What's even more discouraging about TB is how it has a way of thriving on people's ignorance, which spreads slightly faster than the disease itself. The economic benefits of a global community have encouraged the loosening of borders, resulting in more "open" countries. That is, wide open to ineffective health care systems for TB screening and treatment, vulnerable to xenophobic rhetoric, and exposed to more complicated, drug-resistant strains of TB.

Canada is no exception. Despite what some immigration critics in this country seem to think, there's no stopping the movement of people. So what steps have countries like Canada been taking to protect people's health? And are these strides large enough to eradicate TB, or are we taking two steps back from a crisis that's growing in strength? Whatever the situation, no real moves can be made without a clear understanding of what health care workers throughout the world are facing.

Tuberculosis is a highly infectious disease. It can lurk in a person's system for years undetected, and constant exposure to a source increases the risk of contraction. When someone with active TB coughs or sneezes the bacterial infection becomes airborne through moisture droplets. Once inhaled, it multiplies in the lungs and travels in the body through the blood. By the eighth week after infection, the immune system usually stops the spread of the bacteria, but it will remain latent in a person's system for life. A weakened immune system can easily entice TB to become active, making its symptoms contagious.

The disease affects the lungs, prompting coughing fits, fatigue, fever, and weight loss. Blood-streaked saliva or mucous is sometimes a late symptom. The bacillus can also attack the lymphatic system, bones and other tissues, but these situations are less common.

Romantically coined "the people's plague" over a hundred years ago, TB was the disease that killed some of the world's most artistically inclined. They were people such as American writer and poet, Edgar Allen Poe; Polish composer Frederic Chopin; English novelists George Orwell; Emily and her sister, Charlotte, Bronte; American First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt; and American actor Vivien Leigh. Today's survivors include Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and former president of South Africa, Nelson Mandela.

"We had this joke that we need a high-profile person to come down with TB," says Dr. Michael Gardam, the director of the Tuberculosis Clinic at Toronto Western Hospital. His dry tone implies there's nothing funny about what he has called a forgotten epidemic. "Anyone breathing bad air at a bad time can get infected," says Dr.Gardam. "TB doesn't discriminate."

What's frustrating for health workers is the fact that TB is curable. And its vaccine is given to some 100 million newborns each year, making it the most widely used vaccine ever made. Still, health organizations have cited that an astonishing 2 billion people -- a third of the world's population -- may carry a dormant TB infection, with about 10% of them developing a life-threatening form of the disease.

The most complicated challenge is not fighting the existence of TB, rather combating what TB has turned into. The standard TB vaccine apparently is no match for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes the disease. And with this bacterium shifting shape into killer strains, resistant to most powerful drugs, treatment has become a problem for health workers all over the globe. Still, Canada's newly-arrived people have been the target of immigration critics who usually blame refugees from Africa, Asia and South East Asia for CanadaÕs experiences with TB. In July, Diane Francis of The National Post used the latest statistics on TB in Canada to forcefully make her point .

"The average cost of curing drug-resistant TB (in Canada) is $150,000 per person," wrote Francis. "Many of these refugee claimants who are infected disappear, refuse to get treatment and end up infecting Canadians who will also become a burden to the health care system." But Dr.Gardam looks at the situation differently. He, instead, talks about the slow demise of public health programs around the world, as seen in the former Soviet Union, and in parts of Africa.

"Basically, for 20 to 30 years not much was done with TB," says Dr.Gardam. "One of the many problems about this disease is a lot of doctors may not know how to treat it. In North America we've been complacent about it. A doctor may have an infected person sitting in a crowded waiting room, increasing the risk of exposure to other people." The Toronto doctor adds that when he was in medical school, the topic of multi-drug resistant TB was "not touched." Seemed the popular belief was TB no longer existed as a life-threatening disease.

Dr. Gardam's TB clinic, open one year now, operates half a day every week to treat infected patients. It is one of four in the city. Those infected remain in isolation, so as to reduce the spread of the disease to other patients and staff. But despite Canada having one of the lowest rates of TB in the world (about seven TB-positive cases per 100,000 people infected), Toronto has a TB infection rate three times higher than the Canadian average. "We're not a homogeneous society in this city, so we do have pockets."

Dr.Gardam says it's difficult to get a handle on the multiple problems revolving around TB. "Then there's HIV which is a total nightmare." Dr.Gardams voice trails. He explains that in AIDS patients, latent TB has a greater chance of becoming active, and when it does, it destroys a person's system with more severe symptoms. The increasing numbers are staggering. "It's estimated that over 12 million people in the world have both diseases," he cites. "If you're HIV positive, you're more likely to have TB." As well, TB also seems to speed HIV's replication rate, fuelling the onslaught of AIDS more quickly.

Madzima is another person who's not in the blame game. He doesn't point to refugees as the sole reason for the TB resurgence. Having traveled back to Zimbabwe a few times since his move to Canada in 1991, he sees a doctor regularly. "Many people here and in Africa, when they realize they carry TB, they go out and get the right medication. But when they feel better, they stop taking that medication," says Madzima, who has so far, tested negative. He recently had a full physical, which included the Mantoux skin test -- the more popular method of checking for the TB antibodies.

"It's not that people (in Africa) don't do anything. We need constant consultation and therapy." He adds that in some instances, not all the required medication is available, due to a lack of medical resources. Still, renewed hope is on the horizon.

Molecular biology is in the search for the right tools to find a new and improved TB vaccine. For the first time in decades, organizations, institutions and donors are putting up money. In 1998, American researchers made a historic leap when they discovered the DNA for all TB genes. And, ironically, scientists say the escalating death rate of TB-infected people developing AIDS has raised public awareness. In 1993, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared TB a "global health emergency" and the European Union responded by launching a $4.3 million TB vaccine cluster research program in 1999. In the U.S., a $25 million grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation helped drive a new round of vaccine development.

Canada has also taken on the challenge. In March of this year, the federal government announced a contribution of $32.2 million to fight tuberculosis in developing countries. The funds were provided by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) and allocated to prevention and treatment projects in nations like India, Zambia and the Philippines. CIDA's projects have also embraced a hands-on approach. A strategy called directly observed treatment, or DOTS, allows for an observer to watch tuberculosis patients take the required daily medicine. The observer informs the attending doctor if a dose is missed.

But while the funds are being dispersed to countries battling TB, in North America enthusiasm trickles into hospital examination rooms like an intravenous drip. Frontline doctors and nurses are grappling with something that's growing faster than public awareness. It's as Dr. Gardam aptly puts it: "This is big." What is also spreading is fear. It was only in the spring of this year when news of Gaspare Benjamin broke. Having arrived in Canada from the Dominican Republic, Benjamin brought with him a multi-drug resistant strain of tuberculosis. By the time he was diagnosed, his wife had developed active TB, and 35 other people became infected.

Health authorities in Hamilton and Toronto scrambled to track down and screen over 1,000 people who had come into contact with the couple. As it turned out, Benjamin had been tested for the disease, but Canadian immigration officials later admitted that a doctor hired by the ministry had misdiagnosed the chest x-ray. Still, by the time the media was done with the story, xenophobia had reared its head.

As for Madzima, he knows first-hand about a lack of proper health resources in the fight against TB. While visions of success dance around in this artist's head, he can't look ahead without turning back to the people in his homeland. "It's not just about my family. It's about everybody," he says. "In a time of suffering and pain, everybody's family."

Perhaps with the steady crossing of borders in our shrinking global community, a mentality similar to Madzima's will prevail, and once and for all, tuberculosis will dwindle into obscurity. In the mean time, the international effort for its eradication continues.

Produced with the support of the CANADIAN INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY (CIDA)

In Part 3 of WORD's series, Natalia Williams explores the scope of Malaria, one of the world's most deadly environmental diseases.

In Part 4, a look at who gets targeted by Canadian immigration and international organizations in the fight against Tuberculosis.

<Back to top>