The TB Epidemic in a Borderless World

By Natalia Williams

The news release issued by the Toronto Disaster Relief Committee (TDRC) on an early morning last November was searing.

TDRC workers barely masked their outrage after Toronto Public Health quietly released a report the day before that found an unprecedented nine cases of tuberculosis and one TB-related death in a downtown Toronto men's hostel. "This information sends shockwaves through the homeless community, social workers and street nurses," said the release. Given the "relationship between homelessness and TB," it continued, "[w]e and the rest of the community should have been altered to the seriousness of the situation."

A homeless activist group that routinely works with the city's growing homeless population, TDRC workers say they weren't notified of the cases of TB that occurred as far back as spring 2000. Neither were workers at the Tuberculosis Action Group. Essentially the entire network of frontline physicians, nurses and volunteers dealing with the city's homeless population were left in the dark, says Cathy Crowe, a registered nurse with TDRC. "Public Health knows who we are," says Crowe, who has been a street nurse for over 14 years. "None of us were notified." She says news of five new cases and a second TB-related death in December were also happened upon "accidentally."

"I'm quite convinced that the [public health] system is in chaos in terms of TB management," she says.

"The current approach to respond to TB in Toronto and some other cities is archaic."

Sharon Pollack disagrees. Manager of Toronto Public Health's TB program, Pollack says her department is in touch with the latest developments in the areas of TB and communicable diseases. These two outbreaks -- both in number and scope -- are unusual, but Pollack defends Public Health's handing of them. She says a committee of health organizations "weighed it all very carefully" during the first outbreak, before deciding not to issue a general alert, mainly because the infected men "did not socialize" outside of the hostel and the outbreak was "not a danger to the public at this time.

"It's kind of a slippery slope," she adds. "Once this [information] becomes public there can be a real back lash against the community you are trying to help."

Things changed however, when news of the second outbreak became known in late December, and one case had occurred in a different shelter. Then, a release was issued and hospitals and shelters were notified to be on the lookout for TB over the Christmas holidays.

In retrospect, Pollack says she's unsure whether the first outbreak was handled appropriately. She also admits there are resource issues in the department: "It's no doubt that they are stretched to the limit" but she remains confident that the system is ready for any future outbreaks.

However Crowe, and many other experts in the area of infectious diseases, argue this most recent outbreak is a template of a more serious problem: a public health system ill-equipped and ill-prepared to handle today's growing number of communicable diseases. Crowe says news of the TB outbreak never reached the people it should have, when it should have. "It only takes 20 minutes to put together a [news] release and call people," she says. And contact testing, a skin test to determine one's exposure to TB, was not completed on all workers who may have been in contact with the infected men. "There was no proactive screening of the porous community," Crowe says. "The argument is that it's not cost effective."

Experts agree that diseases such as TB and malaria, once thought eradicated, have returned with a vengeance. "A resurgence of infectious diseases has occurred worldwide," says Dr. Kevin Kain, a leading expert in communicable diseases with Toronto Hospital's Tropical Disease Unit. "Every corner of this planet has experienced an infectious disease outbreak of major public health importance within the last decade." We only have to look as far Toronto's recent TB outbreak or to the more widely publicized U.S. cases of west Nile Virus, Ebola and even anthrax to see the haphazard responses these crises.

The reality of a global community is part of the reason for the growing number of infectious diseases. Increased international travel (more than one billion people travel internationally by air each year); more favourable immigration requirements (stalled, perhaps only temporarily, by 9/11); and waves of refugees fleeing war and famine (crossing into neighbouring countries on foot and into distant countries by aircraft), are fuelling what Dr. Kain calls the "globalization of disease."

In an article he wrote two years ago about the subject, Dr. Kain says these threats are only half the reason to be concerned: "The obvious irony is that, just when the threats of globalization of disease and travel-related infections are the greatest, funding, interest and knowledge of these serious health threats appear to be at an all-time low."

About 400 cases of TB crop up in Toronto each year, the most in Canada. Pollack says about 90 per cent of the cases are in foreign-born Canadians. That's because TB is a very common problem in the rest of the world," she says. Aboriginal peoples and the homeless also account for some of the cases each year, but Pollack is quick to add: "You can get a matron in Rosedale with TB as well."

Although frequently the scapegoats, it's incorrect to wholly blame immigrants, argues Dr. Jay Keystone, also with the Tropical Disease Unit at Toronto Hospital.

The reasons are far more complex. Canada welcomes about 250,000 new Canadians into the country each year (about three times the per capita rate of the U.S.), who tend to settle in its main hubs: Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal. Their countries of origin have changed, with more and more coming from developing countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia where infectious disease control is often a losing battle. Before entering the country, immigration officials test for active TB (among other diseases) and then complete follow-ups, as some diseases enter stages of dormancy. In most cases, inactive TB is not a problem, but a University of Toronto study on TB to be released later this year is finding that certain stress factors, such as difficulty finding work and housing, are enough to reactivate dormant TB.

"TB is very opportunistic," says nurse Crowe. And in the wake of 9/11, refugees are being forced back to their home countries -- riddled with war and political strife -- to await a decision on their status. Previously they were able to stay in Canada until the interview date.

Indeed, immigrants and refugees entering the country from areas with troubled health systems do bring some diseases into Canada. But "immigrants and refugees are very little risk to the health of Canadians," says Dr. Keystone. In fact, he considers 250,000 a year a 'drop in the bucket' compared to the over 80 million travelers from around the world who simply step off flights and enter the country unscreened each year. In addition, there are the other 3 to 5 million Canadians who travel to so-called exotic locations each year, ignorant of the diseases they can contract, and ill-prepared by doctors and travel workers who simply don't know to warn them or fear losing a sale. A 1998 study found that almost 60 per cent of Canadians' malaria cases were missed when presented to their doctors. And despite a surge in the number of malaria cases, only about 50 per cent of hospitals were ready to deal with cases of severe malaria.

"The public health system needs more money to carry out surveillance," says Dr. Keystone. They also need an improved knowledge base from which to make a correct diagnosis, followed by the necessary containment. Surveillance. Rapid diagnosis. Containment. It's a three-part concept that Dr. Keystone mentions often as critical to managing what is on route to becoming a bigger problem.

Within this burgeoning concept called globalization is another called global responsibility. Health issues can no longer be defined by within which borders they happen to occur. "Global health is a concept that people have woken up to," says Dr. Kain. ÒWe can no longer think that weÕre protected because we live in the West." Adds Dr. Pollack, "We won't see a decline in TB in Toronto unless you see it globally."

Consider that developing countries make up the large majority of all the countries in the world; Africa, India and China alone account for close to half of the world's population. And according to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 1998 an incredible 99 per cent of the world's births took place in developing countries. Amid this, the world's poor are getting poorer. The famine, poverty and political crises occurring in their worlds cannot be overlooked. Not only for altruistic reasons, but because disproportionate Western wealth is no longer being tolerated.

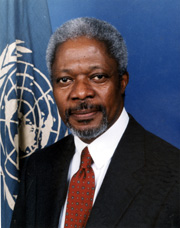

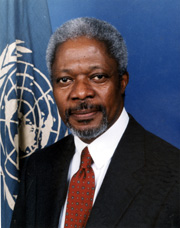

Humans need the basics: food, clothing and shelter. But good health is contingent on attaining all of these. Said UN Secretary General Kofi Annan last year: "We live in an age when the separation between national and international health agendas no longer works. And while poverty lies at the root of many ills, ill health in its turn has a devastating effect on the economies of developing nations."

In that vain, the World Aids Fund was formed last year; the Canadian International Development Agency duly chipped in. In March 2001, CIDA pledged $32.2 million to fight TB in developing countries, namely India, the Philippines and Zambia, filtered through such lofty organizations as World Vision and CARE. And in 2000, it announced $10 million to fight malaria in Africa. More recently, the federal Liberals said they will contribute $500 million over three years to an African aid initiative created last year that has members of the G-8 promising to boost foreign aid to Africa. Whether the money eventually gets to those who need it is another story. It's all far from enough, and only dimly promising, but it's a start.

Yet, beyond the politics, faltering public heath systems, inadequate funding and the stream of promises, it is something in a story Dr. Kain tells that seems to hold a glimmer of a real answer and makes the most sense. He was visiting a remote part of world. There was distrust of him, a white man from the West. One of the men from the area had injured his arm. Dr. Kain offered to look at it. He was able to help the man, while in turn, easing his initial tension and mistrust. "Health is a fantastic ambassador," says Dr. Kain, suddenly a little distant.

"People are able to see directly how it helps them. It forms an instant link."

Produced with the support of the CANADIAN INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY (CIDA)